Introduction

The discourse surrounding globalization has often been shrill, repetitive and emotional – on all sides of the aisle. The proponents point out how trade and growth have increased GDP and living standards, while the critics point out that inequality has grown and the poignant fact that the global biosphere has seen better days, upon which the proponents may claim that the detractors want to deny the developing world the opportunity for raised living standards. There might be acknowledgements that there have been bad effects, but the foundation for the current development is seldom questioned.

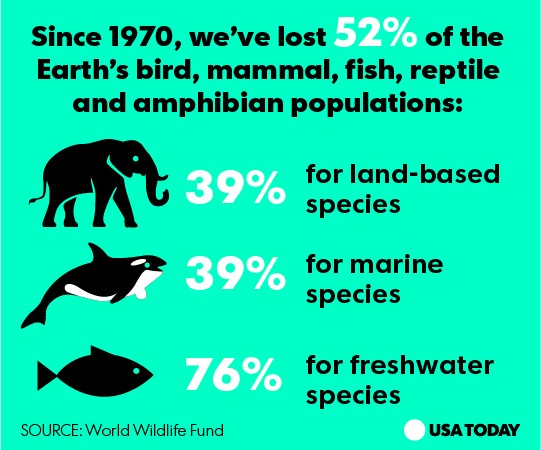

Both sides definitely have points, but where our focus must be centered is on the fact that our current way is inherently unsustainable, and grows more unsustainable with every passing year due to our glaring inability to come to terms with quantitative environmental problems. While many of those in power are worrying for ageing, unemployment, integration or lagging growth numbers within the next two years, the reality we are facing on a global scale is that of an approaching Sixth Mass Extinction Event. In comparison, all other problems appear as minor nuisances.

This article is intended to discuss globalization in terms of different aspects, which can be termed the Good, the Bad and the Ugly – but also try to explore the issue connected to the wider issue of global resource flows. Ultimately, what we all need to do is to let go of our presupposed positions, untangle the web of preferences, aesthetics and politics and look at our world – the only one we have – from a physical perspective. Then, the ways where we can go will reveal themselves.

In short, we need to acquire ourselves a sober, technocratic view on the subject. What we also need is to iterate our line as an organisation on globalisation from our perspective and from the point of view of our ideology and our knowledge about the reality we all are inhabiting.

TL;DR

- Globalization is not a new concept, but is a process which has begun from the moment civilization emerged.

- The current phase of globalization began during the 1970’s with the ascent of new information technologies.

- Like the industrial revolution of the 19th century, it has vastly improved the lives of billions of people.

- Like the industrial revolution of the 19th century, it has also led to increased inequalities across the spectrum within countries – but a convergence between the first world and the developing world.

- Another aspect of globalization is the establishment of multinational corporations with political clout sometimes exceeding that of states.

- Is it likely that this process can continue for the remainder of the 21st century?

Globalization – one process, many aspects

One could say that globalization, roughly speaking, has several aspects. For the purpose of this article we are going to focus on three of its aspects – the technological, economic and political. All of these different developments in their turn have sub-aspects which can affect the world in conserving or disruptive ways. It is also paramount that we understand that globalization is a partially intentional and partially emergent process, much alike most policies enacted by human polities – but on a much grander scale. Therefore, for the sake of clarity, I am going to investigate the three aspects on their own.

The technological aspect

The technologies which are cultivating globalization are generally emerging as innovations within the fields of communication and transport. The first major disruptive technologies within this area were engineered during the early part of the 19th century, with the appearance of the telegraph and railways. These technologies allow the faster transmission of information, people and resources, and are hugely disruptive as they often overhaul local economies and allow for rapid urbanisation and industrialisation. Secluded local economies are connected to the outside world, fostering a process of creative destruction. Meanwhile, it fosters innovation and an opportunity for trading, thus fostering innovation and increased prosperity and opportunities for a larger share of the population, providing – for the first time – choice to people previously relegated to being farmers to build their own lives and change their paths.

Today, the major disruptive technologies are within the sphere of Information and Robotics technologies, which on one hand is de-centralising information spreading and turning every content consumer into a potential content creator (imagine for example the impossibility of such a phenomenon as “Ugandan Knuckles” arising during the 1960’s, when content could only get through more centralised hands).

It must be stated that the technological development of the last two centuries have had many undoubtedly positive effects for human well-being, for health, longevity, child survival rates, maternal care, nourishment, education and living standards, at least for a significant part of the planetary population. That is a proven fact, and our organisation – which strives that human beings should have dignified lives – is viewing the benefits of industrialisation, technological progress and growth in largely positive terms.

The economic aspect

It can be argued that prosperity is a combination of technology, in terms of our ability to harness external energy sources (whether renewable or non-renewable) and the dynamics of an economy. To a large extent, it cannot be denied than the access to cheap credit made possible by the fractional reserve banking system has been a determining factor in creating an environment where investments into innovation have been feasible. This, coupled with public policies of investments into infrastructure, education and healthcare, has during the last 200 years led to an unprecedented increase in the world’s gross product per capita, despite the population growing more than seven-fold since the beginning of the 19th century, and with the exception of a few Sub-Saharan African countries nearly every country on Earth is wealthier today than it was in the year 1818.

This is of course, to a large degree, one of the main reasons why all the health indicators in generally are higher today than in the early 19th century, though it should be stated that even in medium-income countries like Russia, Mexico and Turkey, the average worker today is living a life with better health indicators than most aristocrats did as late as the 18th century, due to better medical technology. That is undeniable.

What, sadly however, also is undeniable, is that economic growth nearly always is following the Pareto principle – that 80% of the new growth is generally tilted towards the one fifth of the population which already is the most economically privileged. This rule is not only prevalent in countries with significant problems of corruption, but in nearly all countries, including most of the large, developed countries. There might be multiple reasons for this, but in general people who have more capital will be more well-connected and have greater options to invest and greater time to judge their options. Wealthier people also in general suffer less stressors which might decrease their performance rate in the economy.

Usually, the political conflict which has dominated the discourse in most democratic states for the last century, has been one between market-oriented liberals and conservatives, who want to grow the economy by free trade and low taxes, and socialists and social liberals on the other side, who want to redistribute wealth from the economically more privileged to the low-income segments of society.

However, the main problem with our current situation from our perspective is more focusing on some key ecological ramifications, which mostly are attributable to how 4100% in global economic growth during only the last century has affected some key ecological ramifications. We will however revisit that.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that according to economic orthodoxy, human needs are perceived as seen through consumption power, which is dependent on a person’s income and savings. All needs are also seen as subjective – so from a purely orthodox viewpoint a Malian woman needing water and rice to survive a month and the “need” of a European male to own a farting clock or a mechanic fish that sings are seen as equal.

The political aspect

Politically, there has since the 1980’s largely been a consensus centred around the market liberal position, that states should ensure that countries open their borders as much as possible for trade, that tariffs must be scrapped and that public companies are inherently less profitable and efficient than private companies exposed to fierce competition. Underlying this has been the presupposition that states must attract and compete for investments, and thus should make their markets as attractive as possible for investors, either through good infrastructure, a well-educated work force or laxer regulations than other countries. The goal is to maximise growth and prevent stagnation, which is a necessity when the monetary systems are built on fiat, and thus are debt based.

The basis for these policies were laid already during the 19th century, with the discovery of Ricardian comparative advantages, and proponents often state that these policies will serve to maximise economic growth and also create a convergence in prosperity between countries.

A lot of the contemporary free trades treaties are doing more than removing trade barriers and deregulating. To a large degree, they are actually restricting the national sovereignty of states by introducing new regulations which often are intended to benefit multinational corporations, with for example increased severity on real and perceived copyright infringements, the so-called ISDS mechanisms (recently declared violating the foundations for European law by the European Court), which means that companies could sue governments for legislation which can harm the profitability of said companies, as well as supranational arbitration courts often very heavily biased towards multinational companies.

Often, this free trade regime incentivises environmental destruction at local and regional levels, and human rights abuses such as sweatshops, child labour, debt slavery amongst rural workers and that natural resources – even vital ones such as fresh water – are owned by foreign companies.

On the other hand, countries like China, India and Brazil have become economic powerhouses thanks to increased investments and mobilization of their resources thanks to foreign capital and the utilisation of their comparative advantages.

While Shanghai, Mumbai and Lagos have benefitted from increased trade, traditional industrial centres in the western world, such as Ruhr, the Rust Belt, Detroit and Liverpool have declined. These free trade policies have accentuated the effects of creative destruction, which have led to increasing inequality within every country involved, giving rise to reactions in the form of left- and right-wing populism. The awareness of this political challenge has prompted the World Economic Forum to recently focus more on social issues, but that focus should be seen as an icing on a cake, or more appropriately said a balm to protect the status quo.

Normatively, these policies are founded both on ideology and on necessity. The necessity is of course the fact that debt is growing faster than the global economy and that the structural imbalances revealed by the 2007-2009 economic crisis still are existing in the economy – coupled with the deeper, inherent self-contradictions of a fiat-based system.

The inherent problem with growth, investments and debt

Most western economies have on general seen their growth rates decrease when the gross domestic product per capita increases. Some countries, such as Japan, seem to already have plateaued, while others are still growing at a modest rate, especially countries with strong markets in real estate and finance. This is not the entire image however, for while a country like Germany may experience a year with 0,5% growth and a country like Ethiopia might experience 5% growth, the 0,5% growth represents – in absolute numbers – far more new economic activity on the side of the developed country. Yet, investments in high-risk high-growth markets yield a higher return for investors, which – together with the comparative benefits of a higher labour pool and often, sadly, less environmental and social regulations, a market attractive for investments.

The reason why larger, developed economies have a lower growth is because investments represent a much smaller share of the entire pie, and also because people stop increasing their consumption exponentially when they reach a certain level of per capita income (which may differ between countries due to differences in cultural preferences).

While the growth in the developed world remains at a modest rate and is slowing down in developing countries such as China, the amount of debt have grown far more during the 2010’s than during the preceding decade. This also accentuates the need for continued growth, because the economies have a desperate need to generate the wealth to pay the interest rates – the inherent problem of a fiat-based global economy (also increasingly challenged by crypto-currencies, though that is a different subject).

In short, even if there were no ecological limitations on our usage of the planet which could impede growth in the future, it is unlikely that growth could go on indefinitely on an infinite planet, except for driven by population growth (which will plateau as well when a country reaches a certain level of development). As infinite planets do not exist (at least not in our Universe) that is just a thought game to entertain.

The Sixth Mass Extinction Event

It is impossible to deny that species are disappearing at an alarming rate, that increased urbanisation is a driver for industrial monocultures which today cover more than a third of the Earth’s land surface, that trawling is devastating to oceanic eco-systems, that the climate is affected by our continued reliance on fossil fuels and fossil-based fertilisers, that insect populations are collapsing and that the amount of forests on the planet are shrinking.

A lot of environmental problems are based on the reliance of certain chemicals and substances which can relatively easily be banned. For example the addition of hormones from medicines and contraceptives into water, the utilisation of neonicotinids (if they are proven without a doubt to be dangerous) and dangerous mine sludge poisoning water reserves can be seen as qualitative problems which can be attributed to practices which can (and often have) been changed by simple political interventions through specific regulations which can be implemented without rocking the foundations of the current system.

You can however not regulate everything and expect to keep the current pro-growth consensus within international bodies. A study by the United Nations show that if we introduced fully compensatory regulations globally, the hundred most profitable industries of today would go bankrupt, and this would run counter to all the ideological values and political judgements by the entire establishment.

The EOS is arguing that the need to transform vibrant ecosystems into high-yield linear mono-cultural production systems is driven by the economic orthodoxy in general and by the foundation of fractional reserve banking in particular, which is based on credit, debt and interest and expects new value to be created. It is also largely a myth that information technology and miniaturization has decreased our resource usage, rather it is still increasing (albeit at a slower rate, but that can equally well be attributable to the fact that growth tends to plateau). Our usage of the world’s surface and resources have also in general increased with growth.

The EOS is also arguing that the destruction of the world’s forests, oceanic habitats, food soils and freshwater reservoirs is increasingly putting humanity before a “global Easter Island scenario”, one where the biosphere is increasingly devastated, creating a convergence of crises and a domino effect where vulnerable regions are turned into collapsed states, and neighbouring countries are increasingly destabilised until billions of human beings are affected. This could, if not amended by Transitionary policies, lead to a new dark age for humanity, with an uncontrolled reduction of living standards, health, democracy and all the values we have learnt to cherish.

According to studies by renowned ecological institutes and universities, we are currently using far more resources than the Earth can renew every year, creating an overshoot and an ecological deficit. Orthodox economists of the neoliberal and libertarian varieties tend to appreciate the ideas of financial budget ceilings. Maybe a global ecological budget ceiling wouldn’t be a bad idea at this point?

The mainstream debate

Though the debate has generally improved and somewhat sobered up following the increasing awareness of how serious our current situation is, the issue of exponential growth and the global biosphere of Earth are still largely treated as mutually independent factors in discourse – politicians can still learn that if we don’t change our relationship with the planet and try to become more sustainable, we will create a collapse, and yet the same evening learn that if we deregulate and globalise further everyone and their mother will be a millionaire by the 2050’s.

These two worldviews are – from any reality-based perspective – incompatible. You have to believe either that growth is decoupled from conversion of environmental areas into linear production areas, that our usage rate of the planet’s surface and of its soil and water has no adverse effects, or that a global environmental collapse would have little impact on our standards of living.

Another popular argument championed by the proponents of the status quo is usually – as my predecessor used to say – “the technology fairy”. The idea in its most inane form is that new technologies will emerge which will solve all the problems, usually by utilising energy more effectively. Jevons’ Paradox, discovered already during the 19th century, shows that the introduction of more energy effective practices often rather can exacerbate resource usage by making it more effective and thus make new and vaster areas accessible for exploitation and assimilation (just look at fracking for example).

Another appeal, in its most crude form is that critics “hate the poor” and do not wish to see increased living standards in the developing world. In its more eloquent, refined form, this critique states that countries need to reach a certain level before the population can start to care about the environment by developing a satisfied and content middle class which cares about conservation. This argument also claims that by focusing on growth, we will have a cheaper and less intrusive transition twenty or thirty years ahead, when new technologies which can clean the air and provide us with virtually free fusion energy can transform the Earth into a green paradise.

Thing is, these claims were made already twenty to thirty years ago, often by the very same proponents of the status quo.

The main problem with that argument is however that the environment is not some kind of staple in a computer game which you can increase and decrease at whim, as if the biosphere was an aspect of human society. It is not just a policy area, such as healthcare, education and infrastructure, where you can cram it into our economy. Rather, our economy is embedded into a roughly speaking 65 million year old natural ecological economy, and is both dependent on it and destroying it.

You cannot near-completely ravage complex, million-year old systems, and then expect to restore everything when you feel sufficiently wealthy to do so. Not unless you live in a world where all environmental systems are just dependent on chemicals, hormones, gasses and pollution – which in reality are not the main problem (excluding our addition of fossil-based carbon).

The socialist alternative

The Alt-globalization movement of the 1990’s had a higher degree of awareness of many of these environmental problems, often coupled with critique regarding the injustices inherent in rising inequality, unemployment and sweatshops. It gathered broad and diverse elements from the entire world who felt threatened by the disruptive effects on both the environment and on the social safety nets.

This movement has lost a lot of its cohesion and steam for the last decades, partially due to what can be labelled “glaring self-contradictions” and the lack of a coherent vision.

- The interests of first world labour laid off from various rust belts are generally not compatible with third world labour which wants to either migrate to the first world to compete for work or export their goods and services to the more capital-rich first world. The Alt-globalization movement tried to unite these disparate interests, but eventually large segments of the unemployed first world proletariat instead moved to the nationalist camp because these were perceived as more exclusively beneficial to their interests.

- While aware of the ecological implications, the Alt-globalization movement selectively chose to ignore these facts when it came to envisioning policies. For example the statement “the current food production of the world can feed x times more billion people than are living on the world today, yet one billion is starving” may be true, but ignores the fact that a significant amount of our current food production is unsustainable.

- Equally, when it came to industry, the Alt-globalization movement simultaneously protested the closure of old factories in the western countries, while condemning pollution caused by factories. They condemned consumerism while vocally defending the right of labour to have professions which were dependent on consumerism for their sustenance.

These self-contradictions were based upon two facts, namely that 1) this “movement” was really an umbrella structure of numerous movements and groups which different and sometimes even conflicting group-egoistical competing interests and 2) that many within the “intelligentsia” of said movement tried to use every conceivable argument they could in the service of ideological (and sometimes emotional) anti-capitalism, ignoring whether the arguments taken together were compatible or even sensible, and maximising the support both amongst workers and environmentalists. This (largely failed) populist strategy could mobilise hundreds of thousands of protesters, but was unable to formulate a coherent alternative.

The EOS critique on globalization

We should, as a movement always strive for the truth.

And the truth is, globalization has brought benefits to billions of human beings worldwide, creating innovation, increasing income, making available the resources for education, healthcare, infrastructure and safety. Neither is globalization a new concept, it began even before the industrial revolution, arguably already during the Ancient era with the establishment of the Silk Road.

As a movement, our Ideology is based on helping Life thrive – and human life and dignity is the central aspect of that. We want every human being to be able to reach their highest potential on a sustainable Earth. We desire for every person on this planet to live their lives knowing they will not become homeless, that they should always be able to go to bed without an empty belly, that their health should be cared for, that they should live without the fear of being oppressed, beaten or exploited and that they should have access to the knowledge and tools they need to realise themselves.

In this regard, we are opposed to inequality when inequality is so stark that it creates a sub-class of excluded or exploited people whose conditions are so damnable that they are threatening to their physical and mental health. In this regard, we should be opposed to all conditions where human beings are deprived of access to what they need to sustain their very lives. Sweatshops and child labour, as well as situations where workers are exposed to dangerous substances, should not exist in the future.

The truth, in today’s world, however, is that the choice for a Chinese factory worker is not between a 12 hour day’s work at Gloxconn and an eight-hour with double the wage and full health benefits, but between Gloxconn and starving unemployment and foreclosure on the countryside.

Before industrialisation, poverty was near universal. And despite the fact that roughly speaking 80% of the growth has gone to the 20% who already have the most decent lives, one cannot deny that life in the beginning of the 19th century was brutish and short, and ridden with toothlessness and early aging for most human beings. That most were illiterate and oppressed farmers who were taught that their only solace lied in death – if they obeyed the spiritual and feudal powers of the elites.

However, the fact that industrialization and globalization clearly have had positive effects, do not mean that we are morally obliged to continue these policies, or that these policies can continue uninterruptedly in the same pace as for the last two centuries.

In fact, our organisation argues that:

- We are transforming the surface of the Earth so much that we are threatening to cause a Sixth Mass Extinction and living beyond our means.

- The reason for that is because we have a fiat-based economic system dependent on debt-on-credit, which forces us to try to increase exponential growth at no matter what cost.

- That exponential growth will always lead to an increase in areas converted into monocultures and linear systems for primarily human usage.

- That the SXE will lead to a global loss of complexity for human societies, driving us down into a new dark age, a Pandora’s box of unforeseeable consequences.

We argue that this is a reality-based assessment of our current situation, and is the single most important issue Humanity has ever faced. The greatest political challenge is to try to establish a balance between our species and the rest of the biosphere it must be a part of if it wants to inhabit this Earth and have a socially, economically and ecologically sound future.

We argue that this can only be accomplished through three criteria.

- A global ecological budget ceiling.

- A global circular blue economy.

- A global covenant of Humanity, that each human being has a right to life and to access for the necessities of life – freedom, housing, food, water, education and healthcare.

In short, the EOS argues that the only way to preserve and create a sustainable basis for our long-term prosperity and happiness as human beings is to make these three criteria the basis of our future civilization.

In my opinion, what logically follows from this outlook is the following positions regarding the three aspects of globalization we talked about in this article.

- Technological progress – we are definitely sympathetic towards technological progress.

- Economic growth – we are not against economic growth, we are against the continued conversion of the Earth’s surface into areas intended to support linear production flows.

- Political globalization – this aspect is problematic, because policies intended to maximise growth and investments are bringing us further away from a genuine Transition. In order to have a necessary Transition, we need a different set of policies with other aims. Our primarily goal should be that the cost of all products should be determined according to their environmental footprint. Policies to increase economic growth in western countries today make little sense, as the populations are stagnating (meaning in the long run that costs on infrastructure maintenance will diminish) and increased incomes have little effect on a population’s happiness when prosperity is growing beyond a certain income level – especially as further increases most likely will mean a heavier weight on the planet and therefore a steeper and much more radical Transition in the long run. There is one aspect of political globalization we should embrace, and that is when we strive towards deeper political integration of regions, and theoretically we should be willing to support the political unification of the entire Northern Hemisphere within maybe a generation.

In short, we are sympathetic to the emergent and organic aspects of globalization, we are critical to our overshoot above the planetary carrying capacity and therefore policies which will increase that impact, albeit unintended. Instead we need a conscious Transition shaped around the fulfilment of the Three Criteria.

Having written that, we should avoid the sloppy broadside critique represented by for example elements of the old Alt-Globalization movement, where globalization is defined wholly by its most repugnant characteristics, the criticism is both progressive and conservative simultaneously and thus irreconcilable with itself and the main ethos seems to be anti-capitalism beyond everything.

Our movement should be defined by love for Life and Humanity, expressed by the aforementioned Three Criteria. As long as we are sustainably capable of reaching the Three Criteria, the exact forms of governance should be determined by their ability to reach the goals, rather than any emotional or aesthetic-optical considerations.

For Life, Love and Light!