Introduction

A common critique of the Design is that it provides a template for how to arrange and structure the future economic system of humanity, without discussing the transition from Capitalism to Energy Accounting.

To some extent, the critique is often coming from various left-wing organisations, but more commonly they come from detractors, who may agree fundamentally with our critique of the current system, but for varying reasons do not believe it is desirable or realistic to completely overhaul the existing order.

Such questions are often not asked in entirely good faith either, but made in order to define the EOS as politically immature and therefore discard not only any eventual lack of transitionary planning but also the Design itself. After all, why the hassle of contemplating an alternative socio-economic system if we do not intend to institute it?

It should be noted that the above-mentioned rhetorical question, based on fallacious assumptions about the lack of a transitionary goal plan of the EOS, also assumes that the representatives of the EOS have the audacity to propose themselves as the leaders of the global future of mankind, and that the EOS fundamentally is striving to assume power. This is an abject absurdity, and based on the notion that human beings can only be motivated by greed or power.

The purpose of this article is to once again reiterate what the purpose of the EOS and the Design is, but also something more – to offer a tangible transition plan in the face of ecological collapse and a situation where the elites of humanity are unable and unwilling to look past Capitalism for answers on how to arrange the relationship of our civilization and the Earth on which it is dependent.

Summary

- Energy Accounting is an economic calculation model designed to the conditions humanity is facing during the 21st century, where 8 billion people must share what a planet with a rapidly deteriorating environment and dwindling resources could provide.

- The EOS is formed around the goal of testing aspects of Energy Accounting and identify how the system responds to real world challenges.

- Thus, the EOS itself does not intend to make this model of a future society come true, but to establish it as an alternative model for social and economic development (look at the article The Only thing we are asking for).

- There are basically two routes to institute Energy Accounting – top-down and bottom-up.

- A bottom-up approach would see a slow, incremental transition of non-state actors combining their productive resources to gradually decouple from the market economy.

- It is fundamentally not only possible but necessary to combine top-down and bottom-up approaches to the transition issue.

- We don’t have much time, but we have to do it.

Energy Accounting and the EOS

Our planet is on a rapid trajectory towards environmental collapse, not only in terms of the climate issue, but on a broad front of interconnected areas such as freshwater deposits, soil erosion, biodiversity, ocean acidification and the spreading of plastics and medicine into the food chain. During the second half of the 20th century, this process became increasingly evident. As a direct response, political, activist and scientific movements aiming to slow down, stop and/or reverse this trend were launched – collectively known as the green movement or the environmentalist movement.

Broadly speaking, this movement can be divided into two subdivisions:

- Those who believe that the environmental crisis primarily is caused by the employment of dirty or subpar technologies, and that capitalism and the current civilization are possible to keep operating under conditions identical or near identical to its current form.

- Those who believe the environmental crisis to be primarily caused by capitalism/consumerism and its imperative for endless growth, and that neither the current civilization nor its economic order is possible to salvage in any form resembling the current model.

The first form of green movement is the one which is prevalent within contemporary green parties, think tanks, green businesses, governments, supranational institutions and scientific institutes. While they believe that consumerism would have to be reduced, they believe primarily in voluntarism and in technological solutions such as renewable energy and electric cars. The most radical faction believe that we might need increased green taxes, and even a shift to more of a welfare state, which they usually call “new economic paradigms”.

The second form is actually consisting of all the other green movements, from eco-socialists and eco-anarchists to deep greens to anarcho-primitivists – movements with visions wildly varying from one another, and only basically agreeing that capitalism is a leading cause towards environmental degradation.

Our movement is the second kind of movement.

Most of the movements and trends which claim that a systemic change is necessary only goes so far as to say that capitalism is impossible to unify with any form of sustainable future for humanity.

A few movements have suggested reforming capitalism or replacing it with other models. Right now, the most popular form of suggestion is known as “Doughnut Economics”.

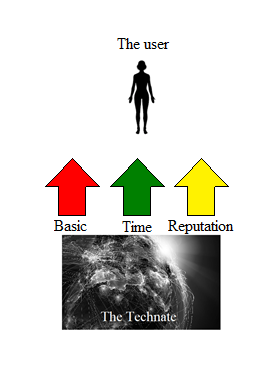

The model proposed by the EOS is known as Energy Accounting, and means the creation of a non-monetary currency which in its total quantity would correspond to the planetary carrying capacity. Unlike money, energy credits would cease to exist after being used and after a specific amount of time, as they represent production capacity allocated. The recipients of the energy credits would be citizens, cooperatives/holons and public utilities/holons. The cost of any product or service would be correspondent to its total energy cost in terms of extraction, refining, assembly, transport and ecological restoration/compensation, meaning that every externality would be internalized.

The human economy cannot and should not exist independent from the planet which provides the human race with all it needs to thrive. The Earth and its biosphere is an integral factor, and any type of developed economic system which does not take into account the way in which it affects the planet is dooming humanity to future hardships.

Unlike Doughnut Economics, Energy Accounting is approaching the issue of economic reform not from the perspective of what our current system is and how it can be amended, but from the needs of the planet itself. In short, we have made a conscious choice to disregard the financial and monetary models as they currently exist and as they historically have evolved, instead treating the Earth as we would have viewed a novel, alien planet, and humanity as we would have viewed ourselves were we to settle that planet.

This poses a challenge, since the description of Energy Accounting disregards any roles whatsoever for any currently existing financial and monetary institutions on the national and international levels (this does not mean they won’t have a role to play, only that the EOS hitherto have not mentioned them), as well as any type of reform which would be conducted through taxation and/or subsidies or the introduction of carbon sequestering markets.

Another challenge with a fully novel model is that we have not yet seen the economic and social effects of its implementation. Therefore, establishing a detailed transition plan would be counter-productive as we do not yet know what kind of timetable and form of implementation would be the most suitable for the establishment of Energy Accounting.

Therefore, the transition by necessity would be composed of three phases.

The Experimental Phase

Energy Accounting could be simulated or tested.

Simulations would be consisting of computer programmes and of games (virtual or analogue), but these would either rely on algorithms with a programmers array of behaviours, or on human participants who would be informed that they are acting within the context of a simulated environment. In either case, the resources managed would be hypothetical and set under conditions which would be determined by the game master.

The knowledge which can be derived from simulations could be important, but must be combined with data from real life field runs – in short testing.

A test of Energy Accounting would be conducted in the real world, and would be formed within the context of a semi-closed network, which would manage key resources in accordance with the principles of Energy Accounting.

Our most common model sees two essential resources being allocated according to the principles of Energy Accounting – electricity and food. A prerequisite is that the network conducting the field test itself produces these resources. Why electricity and food have been chosen is because they are essential for the operation of a human society.

Such a network is called a proto-technate.

An embryonic proto-technate with the intent of testing Energy Accounting would not – contrary to what both detractors and a few supporters instinctually believe – be an isolationist commune totally separated from the wider world, for reasons which are quite obvious but which I will describe in greater detail later in this article.

All resources which it cannot itself acquire would be acquired the normal way on the market, though the network could expand – either by the absorption of new holons, or by the already existing participants diversifying their productive capabilities.

The proto-technate would consist of four functionalities.

- The creation and distribution of energy credits to the holons.

- The holons which manage the production of the utilities.

- A separate company owned by the proto-technate responsible for the import of products and services, and the acquisition of land and productive ability/facilities.

- A system of management which is elected by the participants, and a constitutional charter delineating the rights and limits of the proto-technate in accordance with the Three Criteria, with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and with local laws and prescriptions.

Nothing would prevent several experimental proto-technates to exist concurrently. In that case, the unification of several proto-technates must be considered only if it would improve the ecological, social and infrastructural impact of the technates in question. If two proto-technates are unified, they would be considered as one proto-technate, while the holons consisting the proto-technate will keep their autonomy.

Many proto-technates will encounter challenges, either at their initial phase or at any of the latter phases – and some will fall. The experiences – good and bad – will become the basis for further experimentation with post-monetary economic systems.

The evolutionary phase – defeating the “Life Puzzle”

During the experimental phase, participants would be highly motivated activists and researchers who would be motivated by the desire to test Energy Accounting, judge its implementation and decide whether it is able to survive and outperform the current system on social and environmental sustainability indicators.

The next phase, the evolutionary phase, would see a very different type of participant join in – namely those who join in order to improve their own subjective quality of life. This would not be a problem or something which is needed to be combatted, even if the understanding among these participants about Energy Accounting and its intricacies might initially be very flawed or even non-existent.

The question which we then arrive at would be – what would incentivize people to join a proto-technate?

The answer to this is tied to the paradigm of the experimental phase. Beyond the seeding of a proto-technate, which may indeed be marked by uncertainty of the future and hardships, the holons should not strive towards growth for the sake of growth. If it is possible for a proto-technate to expand its productive capabilities, it must be weighed against the labour time the participants have to put into this expansion, and whether it would consume more labour time in the long-term than prior to the expansion.

In short, the proto-technate should operate for the sake of its participants – and here we come to the term social sustainability.

The electricity and food of the proto-technate would be distributed according to the allocation of energy credits made by the holons and the participants. This means that a significant amount of electricity and food will come for free to the participants. Likewise, those living in buildings owned and operated by the proto-technate would not pay any monetary rent. This will make it possible for people to reduce the amount of time under which they have to work outside of the proto-technate, as their life costs would drop and they would be able to sustain themselves on a smaller income.

In contemporary Sweden, arguably one of the best developed societies on the planet and a progressive lighthouse, one of the most common terms is “the life puzzle”. An ordinary citizen is expected to both have a career and a family life, as well as a successful social life. As a full-time job is for eight hours, and both parents are expected to work, children are generally placed at full-time daycare (and occasionally nightcare) centres, where they are to be picked up by the parents. The hours of the day are usually neatly regimenting themselves, with little time for reflection, rest or pastimes. Due to this stress, especially during the crucial toddler years, relationships are falling apart, and many people are suffering from mental breakdowns over their perceived failure to fulfil the ideal of a successful Swedish citizen.

It should be noted that the workloads of hunter-gatherers or medieval farmers were lighter than for contemporary office workers in developed societies.

Almost everybody are loathing the jigsaw puzzle that is life, but the “life puzzle” is considered a fact of nature in Sweden – almost as natural as rain, air and sunshine.

But what if it wasn’t?

What if people could work less, for a comparable standard of living, and spend more time with their families in a communal setting where they could have more time to live and breathe, where electricity, food and housing would be cheap or virtually free? This would make life in the proto-technate far more agreeable than a comparative life in “normie society”.

Of course, most of the people in the proto-technate would still have regular jobs outside of it, providing taxes to the state. But they would be able to keep more of their income and establish savings as they would not have to pay for utilities – unlike part-time workers in crumbling rental apartments, who would have to put a lot of their monetary earnings into food, electricity and rent.

In short, a system which is intending to create a moneyless society could during its initiation actually make its participants monetarily wealthier. An individual working part-time and living under a proto-technate may theoretically have a larger disposable income in money than an individual who is working eight hours and lives in an ordinary home or apartment.

As the proto-technate expands, this type of discrepancy will grow. Car and machine pools, the ability to acquire clothes, household items, furniture and even homes without any monetary payment will further increase the safety net of those living within a proto-technate, while their actual need for money would decrease. This form of social sustainability would increase individual autonomy and dignity, reduce stress factors and alleviate physical and mental pain. Parents could have more time to spend with their children. Life could become idyllic, calm and rewarding, without fear of economic or social safety.

Of course, many things could go awry during the process.

- The community could collapse due to internal conflicts or other factors.

- The community could succumb to complacency and turn stagnant and inward-looking.

- The community could turn dogmatic and repressive against those who are ideologically objecting or indifferent.

That is why a charter is essential, as it would not only define how positions of responsibility are appointed, term limits and transparency criteria, but also broader ideological and ecological goals. Nevertheless, leeway must be provided that people who join a proto-technate should not need to change or conform to the ideals of the network – our goal is not to create a “new human”, but that humans should be able to be human (rather than hamsters).

The revolutionary phase – the long game

If successful, the proto-technates would gradually both diversify and unify into larger networks, which would work according to the path of least resistance. During this transition, the participants would find that the behaviour they are inclined to adopt given the circumstances would further the cause of Energy Accounting, at the expense of the capitalistic Price System.

At a certain point, people will increasingly stop working inside the regular capitalistic economy, as the proto-technate would be capable of providing their needs – especially with the large-scale adoption of 3D printing and with the increased accessibility to renewables. If this trickle turns into an exodus, it could spark exponential growth for the technate, and also put increasing stress both on states and on private for-profit corporations. On one hand, this trend could incentivize even corporations to collaborate with the proto-technate, acquiring energy and other products in return for their services – while it also could spark a backlash against the proto-technate, and repression from state authorities.

In this sense, the by then tens of thousands of holons comprising the proto-technate would reconfigure and find new methodologies to further their collaboration. In short, it is a long game, a struggle where the holons fight not only for the planet and the Ideology of the Third Millennium, but also for their participants and the wider communities into which they are embedded.

That is also why it is essential that those intent on forming holons try to avoid markers which would be stigmatizing and isolate them from the wider community. Apart from not consciously isolating themselves in communes, they should avoid sporting behaviours or aesthetics which would mark them out as asocial, for example condemning the lifestyle choices of other people, or holier-than-thou social markers. Such choices could initially strengthen the cohesion of the holons, but would defeat the purpose of the struggle. Proselytizing should be avoided, and the learning of Energy Accounting and the Ideology should happen within the holons in the framework of voluntary study circles.

If the holons are viewed positively by the local non-technate communities, and their participants seen as respectable individuals with names, passions and dreams, then attempts of state or group repression against them would either fail or backfire, and help to delegitimize the causes of the detractors of the proto-technate – since what would be seen by the public would be attempts to repress people who desire to live autonomously and to provide for their families.

Another thing which should not be discouraged is for participants in the proto-technate to also take part in civic life in their wider communities. Active participation would not only endear the movement to the public and help in expanding the scope, but also gradually transform the local institutions in a manner conductive for the wider objectives. Nevertheless, political and institutional engagement at the local level must not as its aim have to establish political hegemony, since that would produce hostility and tear apart local society. Rather, the most long-term feasible relationship is one where there is difficult to ascertain where the proto-technate ends and ordinary market society begins. It would reduce the risk for tensions and for resistance to emerge.

Eventually, the proto-technate would not only co-opt institutions, but forming its own academies, universities and think tanks, and start training cadres of professionals who are imbued with the experiences of the Design. This is a long march and a multi-generational project.

Afterword – “But we don’t have time!”

A new 2022 UN report shows that half of the corals of the oceans have died. The world is in a state of an acute crisis. One argument which is often flung against eco-progressive critiques of capitalism is the lack of time. We are following the trajectory of the 1972 Limits to Growth report which would put the collapse of the planetary ecosystems around 2070. Most analysts agree that the tipping point for carbon dioxide reduction to have an impact is this decade, and that the 1,5 degree goal probably already is overdue.

Today, a conflict within the power ranks of the developed world has fully emerged and is polarizing our societies. On the eco-progressive side, there is an alliance consisting of financial-political elites and activist organizations which sees climate change as an existential threat, and which intends to curb it using means within the current system. In general, the activists are not proposing the solutions but rather prefer to leave that to institutions and think tanks such as The Bill & Melinda Gates Founation, or The Stockholm Institute, which nevertheless have more resources to fund studies.

Recently, the Youtube channel Kurzgesagt published a video sponsored by the Gates foundation, describing the foundation’s preferred strategy for the transition. While this topic may be deconstructed in another article, I would be amiss if I would not mention that this statement was not only present in the video but also directly attribute to Bill Gates himself – to the effect that “since the crisis is immediate in scope, we do not have the time to invent a new socio-economic system and replace capitalism, so we have to work within the system.”

It should be noted that climate change currently is a hot topic (often quite literally), but that it is dominating the public perception of what environmental problems the planet currently face. And truth be told, it is an existential threat and one that needs to be addressed. But in the same time, it is a part of a wider problem, which also encompasses soil deterioration, freshwater depletion, biodiversity loss, trawling, the addition of artificial fertilizers to the soil and numerous other environmental crises, local, regional and global. In truth, one could either take the position that these problems are disparate in their point of origin and dependent upon divergent factors, be they technological, social or due to individual error, or that they are systemic. If they are systemic, they may be founded upon two points of origin – the population size of humanity and/or the socio-economic system (these two are not mutually exclusive, but the EOS tends to put a greater emphasis on the socio-economic system, given for example that small developed countries have a greater environmental impact than larger countries on the opposite side of the developmental spectrum, and that the world economy has grown with a factor of over forty times since the early 20th century, whereas the population has only grown eight times, meaning that the economic growth has been five times the population growth).

Granted, Bill Gates is not wrong. The time we have to curb climate change is probably too short a time to rely only on the orderly introduction of a post-capitalist system. This does not, however, mean that we should not concurrently work for such a transition.

Right now, there is a concerted effort by elites in the developed countries to introduce a “Great Reset” of capitalism, which will combine aspects of the 1930’s New Deal, 1990’s style Globalization and new forms of supranational ecological and epidemiological monitoring and “multi-level governance” (which is when policies are shaped on differing institutional levels following more dynamic, almost ad hoc-like procedures with unclear delineations of responsibilities and execution). A lot of this process will contain aspects which are progressive, such as basic income, but a lot of it will also help entrench and strengthen the kind of supranational elites which have been formed during the “Davos era of global capitalism”.

No matter whether the visions presented by the Gates Foundation and those of the World Economic Forum are similar or whether the think tanks have had any communication, we can see that the visions for change presented by the WEF contains a trend towards a greater degree of supranational institutional power, more surveillance of the population and a greater amount of centralized control. Their vision is one of a post-growth capitalism which will guarantee some basic income, while at the same time entrench those very elites which are valuing long-term investments before short-sighted gains, and would want to see the planet continue, while at they – for quite obvious reasons – are emotionally attached to capitalism and largely unable to imagine any other alternate system.

The kind of system presented by these think tanks could at best be described as “transitionary”, but there is no clarity to where the transition is heading – if anywhere. There are several reasons why established academia and institutions would not look into the exploration of post-capitalist ideas and models. The challenge comes when we are pulled deeper and deeper into an existential ecological crisis, and the experts assigned to deal with the problem are only capable of thinking within the framework of capitalism, and all their tools which they are equipped with presuppose the continued existence of a growth-based system with a fiat currency.

This is why every movement which is making serious research about post-capitalist models is doing an invaluable work, and why those movements should be supported – because the institutions through which power flows are not interested in widening the options we have accessible to the point that those solutions threaten the existence of these institutions in their contemporary form.

The only thing the EOS is asking for, is your help in developing and testing Energy Accounting, or other alternatives to capitalism designed to create an ecologically sustainable future.

The model which we have envisioned is decentralized, built on putting the control of the future institutions directly into the hands of the people, and on finding ways to compensate the potential inconveniences of a more ecologically sustainable future with a higher degree of social sustainability.

In short, the urgency of the current situation and the unsustainability of the current model is an insufficient excuse to not explore alternatives to said model, and since there already are movements pursuing this course, these movements should be supported as well in conducting their experiments and research.

Excluding them from the public view is tantamount to rather see humanity collapse into a new dark age than potentially entering a post-capitalist future.

![ProtoPic1[1]](https://eosprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ProtoPic11-1700x956.jpg)

![EnergyU1[1]](https://eosprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/EnergyU11-1700x956.jpg)

![Tran[1]](https://eosprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Tran1-1700x956.jpg)

![tec[1]](https://eosprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/tec1-1700x956.jpg)

![WIN_20170404_17_58_35_Pro[1]](https://eosprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/WIN_20170404_17_58_35_Pro1-1700x956.jpg)